# AST Analysis

To analyze Kotlin and Java files, lint offers many convenience callbacks

to make it simple to accomplish common tasks:

* Check calls to a particular method name

* Instantiating a particular class

* Extending a particular super class or interface

* Using a particular annotation, or calling an annotated method

And more. See the `SourceCodeScanner` interface for more information.

It also has various helpers, such as a `ConstantEvaluator` and a

`DataFlowAnalyzer` to help analyze code.

But in some cases, you'll need to dig in and analyze the “AST” yourself.

## AST Analysis

AST is short for “Abstract Syntax Tree” -- a tree representation of the

source code. Consider the following very simple Java program:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~java

// MyTest.java

package test.pkg;

public class MyTest {

String s = "hello";

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

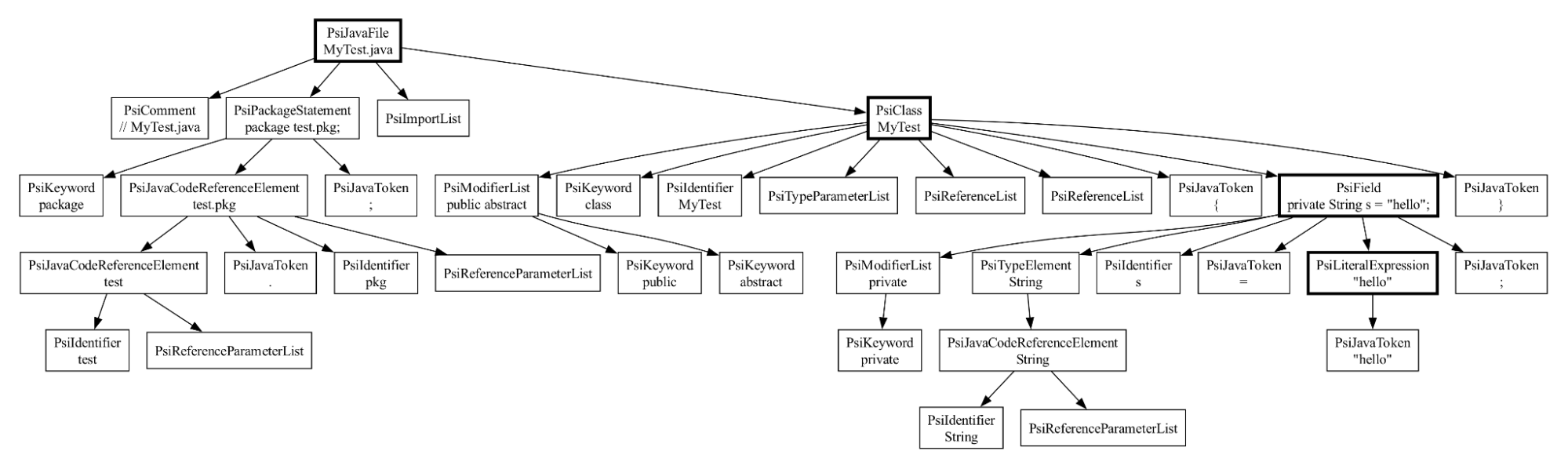

Here's the AST for the above program, the way it's represented

internally in IntelliJ.

This is actually a simplified view; in reality, there are also

whitespace nodes tracking all the spans of whitespace characters between

these nodes.

Anyway, you can see there is quite a bit of detail here -- tracking

things like the keywords, the variables, references to for example the

package -- and higher level concepts like a class and a field, which I've

marked with a thicker border.

Here's the corresponding Kotlin program:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

// MyTest.kt

package test.pkg

class MyTest {

val s: String = "hello"

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

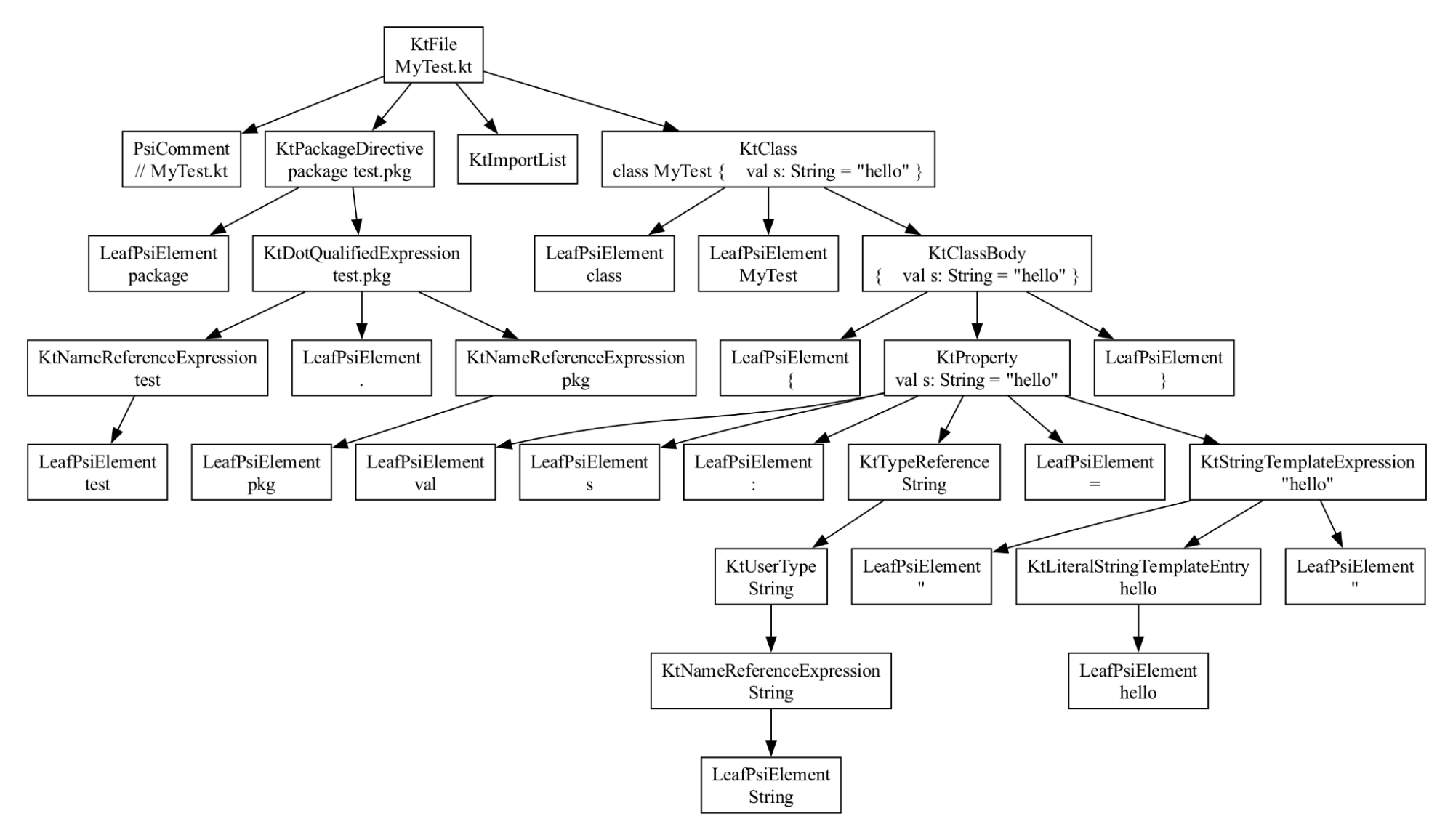

And here's the corresponding AST in IntelliJ:

This program is equivalent to the Java one.

But notice that it has a completely different shape! They reference

different element classes, `PsiClass` versus `KtClass`, and on and on

all the way down.

But there's some commonality -- they each have a node for the file, for

the class, for the field, and for the initial value, the string.

## UAST

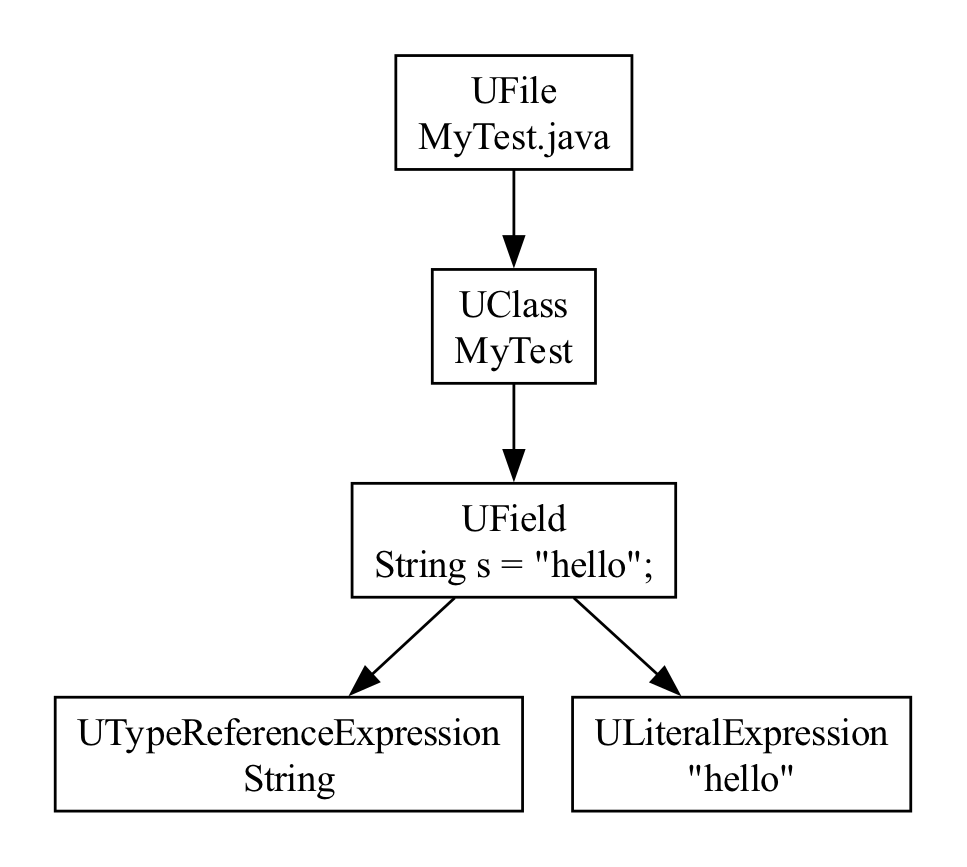

We can construct a new AST that represents the same concepts:

This is a unified AST, in something called “UAST”, short for Unified

Abstract Syntax Tree. UAST is the primary AST representation we use for

code in Lint. All the node classes here are prefixed with a capital U,

for UAST. And this is the UAST for the first Java file example above.

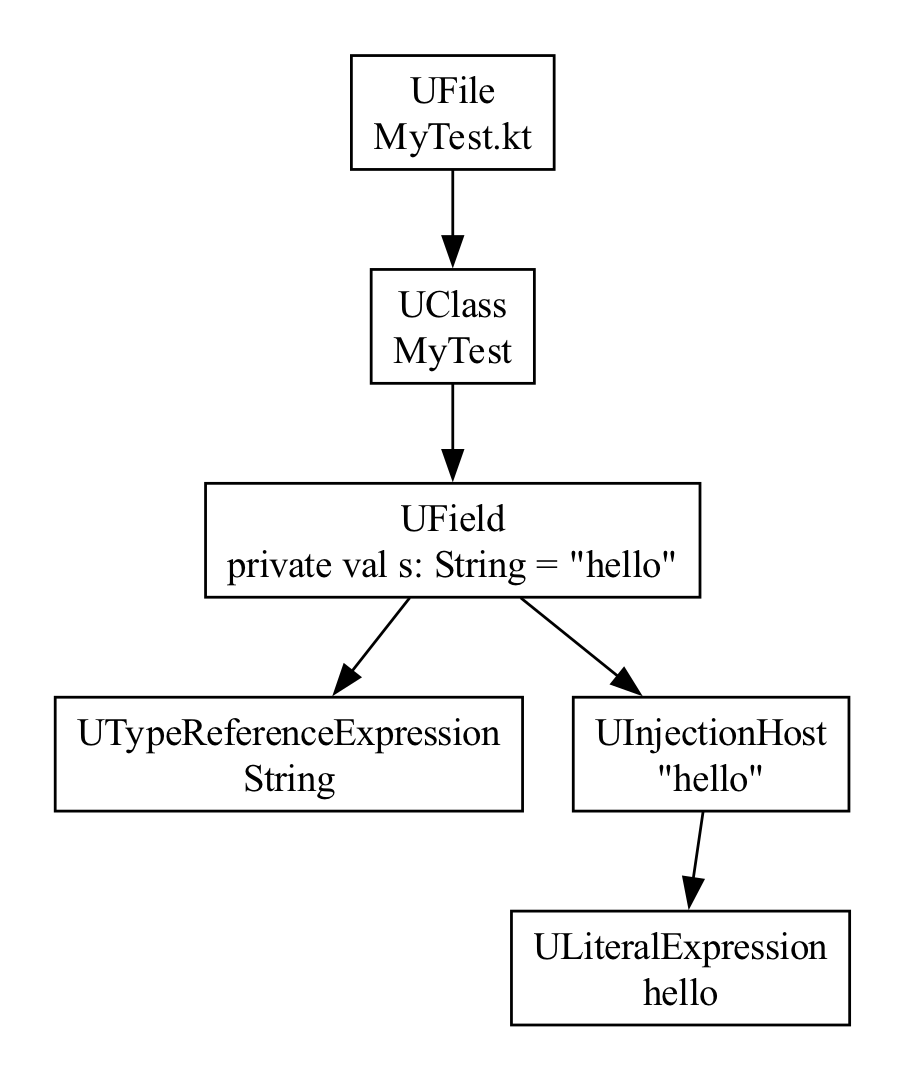

Here's the UAST for the corresponding Kotlin example:

As you can see, the ASTs are not always identical. For Strings, in

Kotlin, we often end up with an extra parent `UInjectionHost`. But for

our purposes, you can see that the ASTs are mostly the same, so if you

handle the Kotlin scenario, you'll handle the Java ones too.

## UAST: The Java View

Note that “Unified” in the name here is a bit misleading. From the name

you may assume that this is some sort of superset of the ASTs across

languages -- an AST that can represent everything needed by all

languages. But that's not the case! Instead, a better way to think of it

is as the **Java view** of the AST.

If you for example have the following Kotlin data class:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

data class Person(

var id: String,

var name: String

)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This is a Kotlin data class with two properties. So you might expect

that UAST would have a way to represent these concepts. This should

be a `UDataClass` with two `UProperty` children, right?

But Java doesn't support properties. If you try to access a `Person`

instance from Java, you'll notice that it exposes a number of public

methods that you don't see there in the Kotlin code -- in addition to

`getId`, `setId`, `getName` and `setName`, there's also `component1` and

`component2` (for destructuring), and `copy`.

These methods are directly callable from Java, so they show up in UAST,

and your analysis can reason about them.

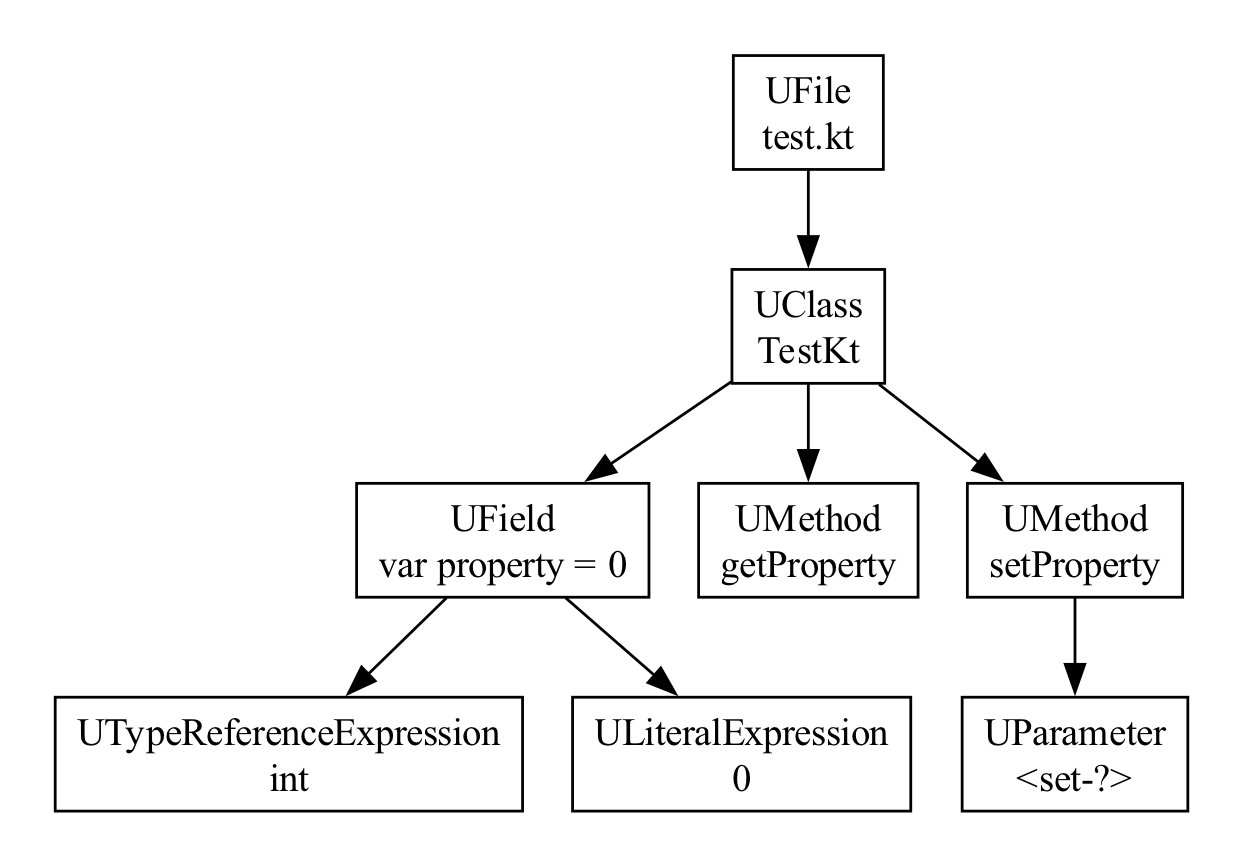

Consider another complete Kotlin source file, `test.kt`:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

var property = 0

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here's the UAST representation:

Here we have a very simple Kotlin file -- for a single Kotlin property.

But notice at the UAST level, there's no such thing as top level methods

and properties. In Java, everything is a class, so `kotlinc` will create

a “facade class”, using the filename plus “Kt”. So we see our `TestKt`

class. And there are three members here. There's the getter and the

setter for this property, as `getProperty` and `setProperty`. And then

there is the private field itself, where the property is stored.

This all shows up in UAST. It's the Java view of the Kotlin code. This

may seem limiting, but in practice, for most lint checks, this is

actually what you want. This makes it easy to reason about calls to APIs

and so on.

## Expressions

You may be getting the impression that the UAST tree is very shallow and

only represents high level declarations, like files, classes, methods

and properties.

That's not the case. While it **does** skip low-level, language-specific

details things like whitespace nodes and individual keyword nodes, all

the various expression types are represented and can be reasoned about.

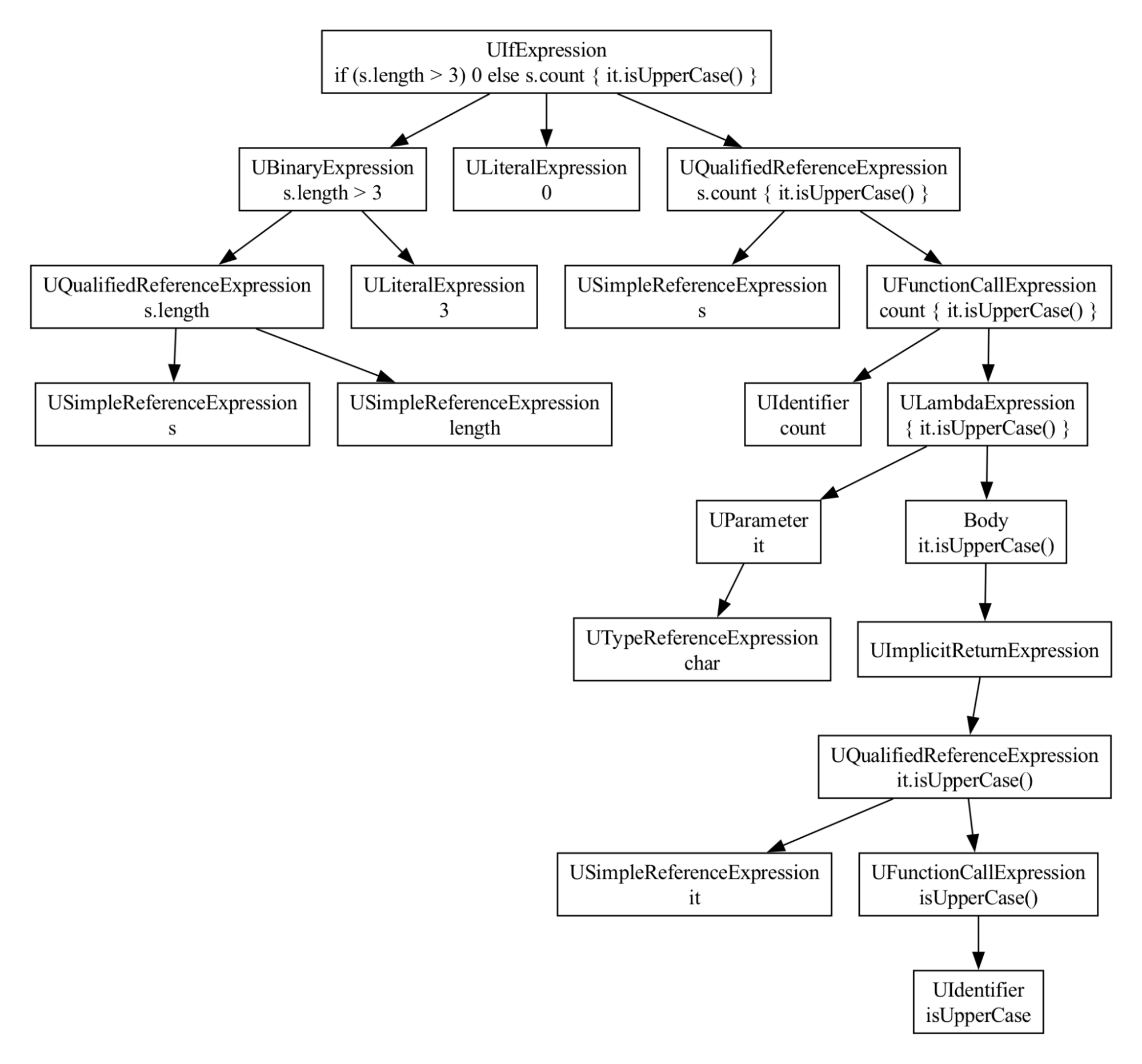

Take the following expression:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (s.length > 3) 0 else s.count { it.isUpperCase() }

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This maps to the following UAST tree:

As you can see it's modeling the if, the comparison, the lambda, and so

on.

## UElement

Every node in UAST is a subclass of a `UElement`. There's a parent

pointer, which is handy for navigating around in the AST.

The real skill you need for writing lint checks is understanding the

AST, and then doing pattern matching on it. And a simple trick for this

is to create the Kotlin or Java code you want, in a unit test, and then

in your detector, recursively print out the UAST as a tree.

Or in the debugger, anytime you have a `UElement`, you can call

`UElement.asRecursiveLogString` on it, evaluate and see what you find.

For example, for the following Kotlin code:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

import java.util.Date

fun test() {

val warn1 = Date()

val ok = Date(0L)

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

here's the corresponding UAST `asRecursiveLogString` output:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~text

UFile (package = )

UImportStatement (isOnDemand = false)

UClass (name = JavaTest)

UMethod (name = test)

UBlockExpression

UDeclarationsExpression

ULocalVariable (name = warn1)

UCallExpression (kind = UastCallKind(name='constructor_call'), …

USimpleNameReferenceExpression (identifier = Date)

UDeclarationsExpression

ULocalVariable (name = ok)

UCallExpression (kind = UastCallKind(name='constructor_call'), …

USimpleNameReferenceExpression (identifier = Date)

ULiteralExpression (value = 0)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

## Visiting

You generally shouldn't visit a source file on your own. Lint has a

special `UElementHandler` for that, which is used to ensure we don't

repeat visiting a source file thousands of times, one per detector.

But when you're doing local analysis, you sometimes need to visit a

subtree.

To do that, just extend `AbstractUastVisitor` and pass the visitor to

the `accept` method of the corresponding `UElement`.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

method.accept(object : AbstractUastVisitor() {

override fun visitSimpleNameReferenceExpression(node: USimpleNameReferenceExpression): Boolean {

// your code here

return super.visitSimpleNameReferenceExpression(node)

}

})

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In a visitor, you generally want to call `super` as shown above. You can

also `return true` if you've “seen enough” and can stop visiting the

remainder of the AST.

If you're visiting Java PSI elements, you use a

`JavaRecursiveElementVisitor`, and in Kotlin PSI, use a `KtTreeVisitor`.

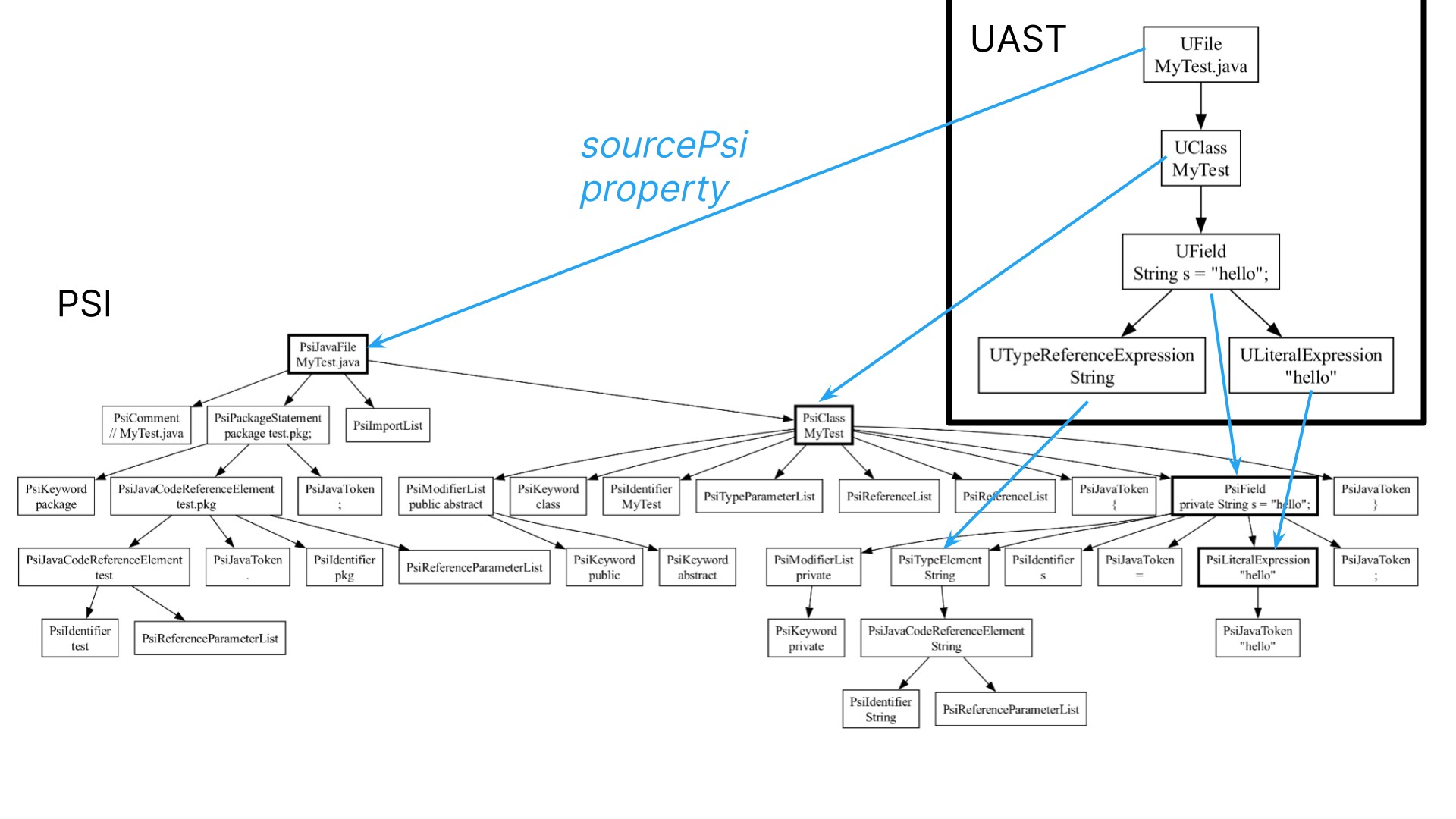

## UElement to PSI Mapping

UAST is built on top of PSI, and each `UElement` has a `sourcePsi`

property (which may be null). This lets you map from the general UAST

node, down to the specific PSI elements.

Here's an illustration of that:

We have our UAST tree in the top right corner. And here's the Java PSI

AST behind the scenes. We can access the underlying PSI node for a

`UElement` by accessing the `sourcePsi` property. So when you do need to dip

into something language specific, that's trivial to do.

Note that in some cases, these references are null.

Most `UElement` nodes point back to the PSI AST - whether a Java

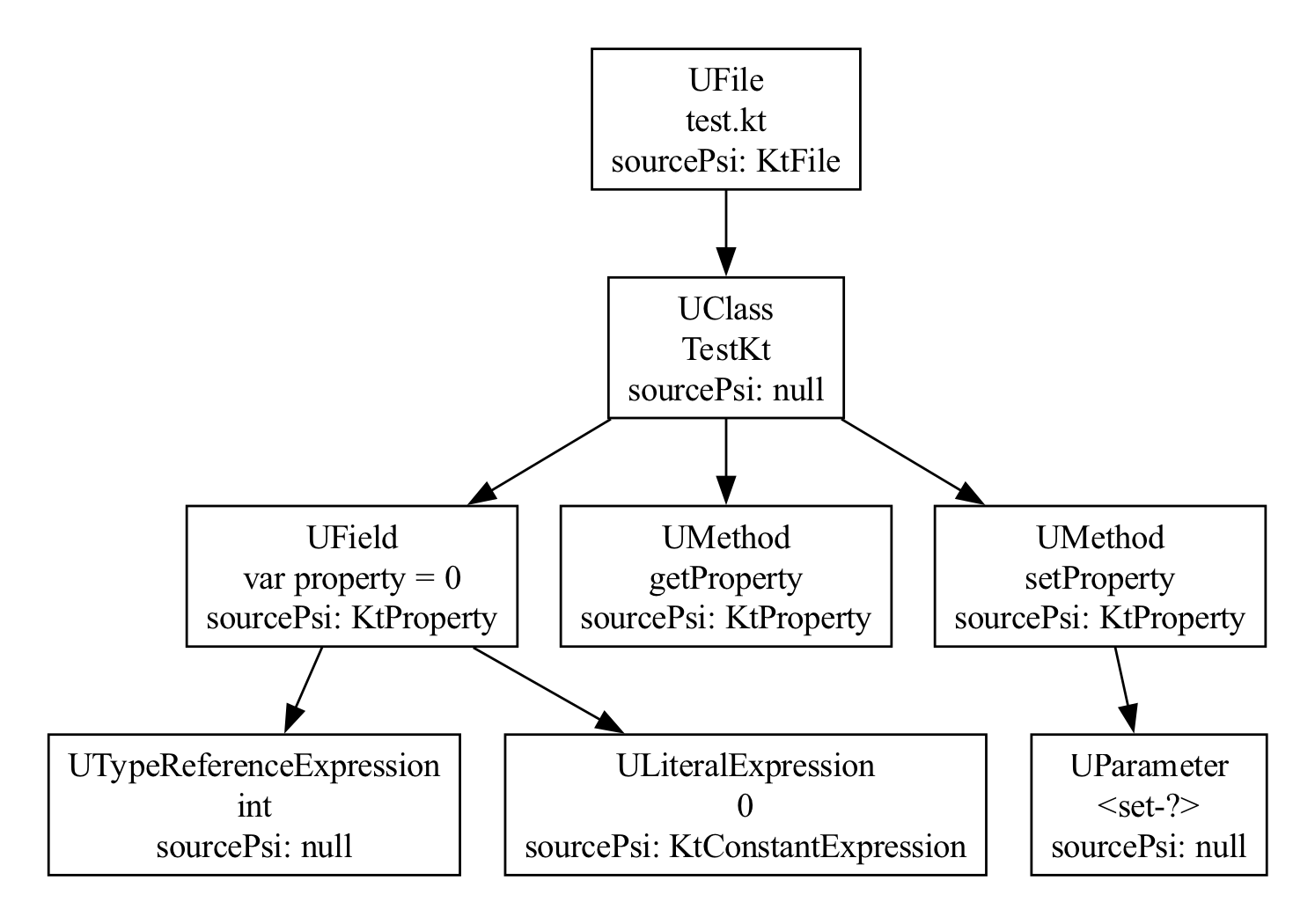

AST or a Kotlin AST. Here's the same AST, but with the **type** of the

`sourcePsi` property for each node added.

You can see that the facade class generated to contain the top level

functions has a null `sourcePsi`, because in the

Kotlin PSI, there is no real `KtClass` for a facade class. And for the

three members, the private field and the getter and the setter, they all

correspond to the exact same, single `KtProperty` instance, the single

node in the Kotlin PSI that these methods were generated from.

## PSI to UElement

In some cases, we can also map back to UAST from PSI elements, using the `toUElement` extension function.

For example, let's say we resolve a method call. This returns a

`PsiMethod`, not a `UMethod`. But we can get the corresponding `UMethod`

using the following:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val resolved = call.resolve() ?: return

val uDeclaration = resolve.toUElement()

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Note however that `toUElement` may return null. For example, if you've

resolved to a method call that is compiled (which you can check using

`resolved is PsiCompiledElement`), UAST cannot convert it.

## UAST versus PSI

UAST is the preferred AST to use when you're writing lint checks for

Kotlin and Java. It lets you reason about things that are the same

across the languages. Declarations. Function calls. Super classes.

Assignments. If expressions. Return statements. And on and on.

There *are* lint checks that are language specific -- for example, if

you write a lint check that forbids the use of companion objects -- in

that case, there's no big advantage to using UAST over PSI; it's only

ever going to run on Kotlin code. (Note however that lint's APIs and

convenience callbacks are all targeting UAST, so it's easier to write

UAST lint checks even for the language-specific checks.)

The vast majority of lint checks however aren't language specific,

they're **API** or bug pattern specific. And if the API can be called

from Java, you want your lint check to not only flag problems in Kotlin,

but in Java code as well. You don't want to have to write the lint check

twice -- so if you use UAST, a single lint check can work for both. But

while you generally want to use UAST for your analysis (and lint's APIs

are generally oriented around UAST), there **are** cases where it's

appropriate to dip into PSI.

In particular, you should use PSI when you're doing something highly

language specific, and where the language details aren't exposed in UAST.

For example, let's say you need to determine if a `UClass` is a Kotlin

“companion object”. You could cheat and look at the class name to see if

it's “Companion”. But that's not quite right; in Kotlin you can

specify a custom companion object name, and of course users are free

to create classes named “Companion” that aren't companion objects:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

class Test {

companion object MyName { // Companion object not named "Companion"!

}

object Companion { // Named "Companion" but not a companion object!

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The right way to do this is using Kotlin PSI, via the

`UElement.sourcePsi` property:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

// Skip companion objects

val source = node.sourcePsi

if (source is KtObjectDeclaration && source.isCompanion()) {

return

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(To figure out how to write the above code, use a debugger on a test

case and look at the `UClass.sourcePsi` property; you'll discover that

it's some subclass of `KtObjectDeclaration`; look up its most general

super interface or class, and then use code completion to discover

available APIs, such as `isCompanion()`.)

## Kotlin Analysis API

Using Kotlin PSI was the state of the art for correctly analyzing Kotlin

code until recently. But when you look at the PSI, you'll discover that

some things are really hard to accomplish -- in particular, resolving

reference, and dealing with Kotlin types.

Lint doesn't actually give you access to everything you need if you want

to try to look up types in Kotlin PSI; you need something called the

“binding context”, which is not exposed anywhere! And this omission is

deliberate, because this is an implementation detail of the old

compiler. The future is K2; a complete rewrite of the compiler front

end, which is no longer using the old binding context. And as part of

the tooling support for K2, there's a new API called the “Kotlin

Analysis API” you can use to dig into details about Kotlin.

For most lint checks, you should just use UAST if you can. But when you

need to know really **detailed** Kotlin information, especially around

types, and smart casts, and null inference, and so on, the Kotlin

Analysis API is your best friend (and only option...)

!!! WARNING

The Kotlin Analysis API is not yet final and may continue to change.

In fact, most of the symbols have been renamed recently. For example,

the `KtAnalysisSession` returned by `analyze`, has been renamed

`KaSession`. Most APIs now have the prefix `Ka`.

### Nothing Type?

Here's a simple example:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

fun testTodo() {

if (SDK_INT < 11) {

TODO() // never returns

}

val actionBar = getActionBar() // OK - SDK_INT must be >= 11 !

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here we have a scenario where we know that the TODO call will never

return, and lint can take advantage of that when analyzing the control

flow -- in particular, it should understand that after the TODO() call

there's no chance of fallthrough, so it can conclude that SDK_INT must

be at least 11 after the if block.

The way the Kotlin compiler can reason about this is that the `TODO`

method in the standard library has a return type of `Nothing`.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

@kotlin.internal.InlineOnly

public inline fun TODO(): Nothing = throw NotImplementedError()

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The `Nothing` return type means it will never return.

Before the Kotlin lint analysis API, lint didn't have a way to reason

about the `Nothing` type. UAST only returns Java types, which maps to

void. So instead, lint had an ugly hack that just hardcoded well known

names of methods that don't return:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (nextStatement is UCallExpression) {

val methodName = nextStatement.methodName

if (methodName == "fail" || methodName == "error" || methodName == "TODO") {

return true

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

However, with the Kotlin analysis API, this is easy:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin linenumbers

fun callNeverReturns(call: UCallExpression): Boolean {

val sourcePsi = call.sourcePsi as? KtCallExpression ?: return false

analyze(sourcePsi) {

val callInfo = sourcePsi.resolveToCall() ?: return false

val returnType = callInfo.singleFunctionCallOrNull()?.symbol?.returnType

return returnType != null && returnType.isNothingType

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin linenumbers

/**

* Returns true if this [call] node calls a method known to never

* return, such as Kotlin's standard library method "error".

*/

fun callNeverReturns(call: UCallExpression): Boolean {

val sourcePsi = call.sourcePsi as? KtCallExpression ?: return false

analyze(sourcePsi) {

val callInfo = sourcePsi.resolveCall() ?: return false

val returnType = callInfo.singleFunctionCallOrNull()?.symbol?.returnType

return returnType != null && returnType.isNothing

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The entry point to all Kotlin Analysis API usages is to call the

`analyze` method (see line 7) and pass in a Kotlin PSI element. This

creates an “analysis session”. **It's very important that you don't leak

objects from inside the session out of it** -- to avoid memory leaks and

other problems. If you do need to hold on to a symbol and compare later,

you can create a special symbol pointer.

Anyway, there's a huge number of extension methods that take an analysis

session as receiver, so inside the lambda on lines 7 to 13, there are

many new methods available.

Here, we have a `KtCallExpression`, and inside the `analyze` block we

can call `resolveCall()` on it to reach the called method's symbol.

Similarly, on a `KtDeclaration` (such as a named function or property) I

can call `.symbol` to get the symbol for that method or property, to

for example look up parameter information. And on a `KtExpression` (such

as an if statement) I can call `.expressionType` to get the Kotlin type.

`KaSymbol` and `KaType` are the basic primitives we're working with in

the Kotlin Analysis API. There are a number of subclasses of symbol,

such as `KaFileSymbol`, `KaFunctionSymbol`, `KaClassSymbol`, and

so on.

In the new implementation of `callNeverReturns`, we resolve the call,

look up the corresponding function, which of course is a `KaSymbol`

itself, and from that we get the return type, and then we can just check

if it's the `Nothing` type.

And this API works both with the old Kotlin compiler, used in lint right

now, and K2, which can be turned on via a flag and will soon be the

default (and may well be the default when you read this; we don't always

remember to update the documentation...)

### Compiled Metadata

Accessing Kotlin-specific knowledge not available via Kotlin PSI is one

use for the analysis API.

Another big advantage of the Kotlin analysis API is that it gives you

access to reason about compiled Kotlin code, in the same way that the

compiler does.

Normally, when you resolve with UAST, you just get a plain `PsiMethod`

back. For example, if we have a reference to

`kotlin.text.HexFormat.Companion`, and we resolve it in UAST, we get a

`PsiMethod` back. This is **not** a Kotlin PSI element, so our earlier

code to check if this is a companion object (`source is

KtObjectDeclaration && source.isCompanion()`) does not work -- the first

instance check fails. These compiled `PsiElement`s do not give us access

to any of the special Kotlin payload we can usually check on

`KtElement`s -- modifiers like `inline` or `infix`, default parameters,

and so on.

The analysis API handles this properly, even for compiled code. In fact,

the earlier implementation of checking for the `Nothing` type

demonstrated this, because the methods it's analyzing from the Kotlin

standard library (`error`, `TODO`, and so on), are all compiled classes

in the Kotlin standard library jar file!

Therefore, yes, we can use Kotlin PSI to check if a class is a companion

object if we actually have the source code for the class. But if we're

resolving a *reference* to a class, using the Kotlin analysis API is

better; it will work for both source and compiled:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

symbol is KaClassSymbol && symbol.classKind == KaClassKind.COMPANION_OBJECT

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

symbol is KtClassOrObjectSymbol && symbol.classKind == KtClassKind.COMPANION_OBJECT

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#### Kotlin Analysis API Howto

When you're using K2 with lint, a lot of UAST's handling of resolve and

types in Kotlin is actually using the analysis API behind the scenes.

If you for example have a Kotlin PSI `KtThisExpression`, and you want to

understand how to resolve the `this` reference to another PSI element,

write the following Kotlin UAST code:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

thisReference.toUElement()?.tryResolve()

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

You can now use a debugger to step into the `tryResolve` call, and

you'll eventually wind up in code using the Kotlin Analysis API to look

it up, and as it turns out, here's how:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

analyze(expression) {

val reference = expression.getTargetLabel()?.mainReference

?: expression.instanceReference.mainReference

val psi = reference.resolveToSymbol()?.psi

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Configuring lint to use K2

To use K2 from a unit test, you can use the following lint test task override:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

override fun lint(): TestLintTask {

return super.lint().configureOptions { flags -> flags.setUseK2Uast(true) }

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Outside of tests, you can also set the `-Dlint.use.fir.uast=true` system property in your run configurations.

Note that at some point this flag may go away since we'll be switching

over to K2 completely.

## API Compatibility

Versions of lint before 8.7.0-alpha04 used an older version of the

analysis API. If your lint check is building against these older

versions, you need to use the older names and APIs, such as

`KtSymbol` and `KtType` instead of `KaSymbol` and `KaType`.

The analysis API isn't stable, and changed significantly between

these versions. The hope/plan is for the API to be stable soon, such

that you can start using the analysis API in lint checks and have it

work with future versions of lint.

For now, lint uses a special bytecode rewriter on the fly to try to

automatically migrate compiled lint checks using the older API, but

this doesn't handle all corner cases, so the best path forward is to

use the new APIs. In the below recipes, we're temporarily showing both

the new and the old versions.

## Recipes

Here are various other Kotlin Analysis scenarios and potential solutions:

### Resolve a function call

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val call: KtCallExpression

…

analyze(call) {

val callInfo = call.resolveToCall() ?: return null

val symbol: KaFunctionSymbol? = callInfo.singleFunctionCallOrNull()?.symbol

?: callInfo.singleConstructorCallOrNull()?.symbol

?: callInfo.singleCallOrNull()?.symbol

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val call: KtCallExpression

…

analyze(call) {

val callInfo = call.resolveCall()

if (callInfo != null) {

val symbol: KtFunctionLikeSymbol = callInfo.singleFunctionCallOrNull()?.symbol

?: callInfo.singleConstructorCallOrNull()?.symbol

?: callInfo.singleCallOrNull()?.symbol

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Resolve a variable reference

Also use `resolveCall`, though it's not really a call:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val expression: KtNameReferenceExpression

…

analyze(expression) {

val symbol: KaVariableSymbol? = expression.resolveToCall()?.singleVariableAccessCall()?.symbol

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val expression: KtNameReferenceExpression

…

analyze(expression) {

val symbol: KtVariableLikeSymbol = expression.resolveCall()?.singleVariableAccessCall()?.symbol

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Get the containing class of a symbol

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val containingSymbol = symbol.containingSymbol

if (containingSymbol is KaNamedClassSymbol) {

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val containingSymbol = symbol.getContainingSymbol()

if (containingSymbol is KtNamedClassOrObjectSymbol) {

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Get the fully qualified name of a class

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val containing = declarationSymbol.containingSymbol

if (containing is KaClassSymbol) {

val fqn = containing.classId?.asSingleFqName()

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val containing = declarationSymbol.getContainingSymbol()

if (containing is KtClassOrObjectSymbol) {

val fqn = containing.classIdIfNonLocal?.asSingleFqName()

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Look up the deprecation status of a symbol

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (symbol is KaDeclarationSymbol) {

symbol.deprecationStatus?.let { … }

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (symbol is KtDeclarationSymbol) {

symbol.deprecationStatus?.let { … }

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Look up visibility

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (symbol is KaDeclarationSymbol) {

if (!isPublicApi(symbol)) {

…

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (symbol is KtSymbolWithVisibility) {

val visibility = symbol.visibility

if (!visibility.isPublicAPI) {

…

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Get the KtType of a class symbol

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (symbol is KaNamedClassSymbol) {

val type = symbol.defaultType

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

containingSymbol.buildSelfClassType()

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Resolve a KtType into a class

Example: is this `KtParameter` pointing to an interface?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

analyze(ktParameter) {

val parameterSymbol = ktParameter.symbol

val returnType = parameterSymbol.returnType

val typeSymbol = returnType.expandedSymbol

if (typeSymbol is KaClassSymbol) {

val classKind = typeSymbol.classKind

if (classKind == KaClassKind.INTERFACE) {

…

}

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

analyze(ktParameter) {

val parameterSymbol = ktParameter.getParameterSymbol()

val returnType = parameterSymbol.returnType

val typeSymbol = returnType.expandedClassSymbol

if (typeSymbol is KtClassOrObjectSymbol) {

val classKind = typeSymbol.classKind

if (classKind == KtClassKind.INTERFACE) {

…

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### See if two types refer to the same raw class (erasure):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (type1 is KaClassType && type2 is KaClassType &&

type1.classId == type2.classId

) {

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (type1 is KtNonErrorClassType && type2 is KtNonErrorClassType &&

type1.classId == type2.classId) {

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### For an extension method, get the receiver type:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (declarationSymbol is KaNamedFunctionSymbol) {

val declarationReceiverType = declarationSymbol.receiverParameter?.type

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

if (declarationSymbol is KtFunctionSymbol) {

val declarationReceiverType = declarationSymbol.receiverParameter?.type

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

### Get the PsiFile containing a symbol declaration

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val file = symbol.containingFile

if (file != null) {

val psi = file.psi

if (psi is PsiFile) {

…

}

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~kotlin

val file = symbol.getContainingFileSymbol()

if (file is KtFileSymbol) {

val psi = file.psi

if (psi is PsiFile) {

…

}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~